I have a huge box full of my medical files, which were due to be used as evidence when my case went to court. Thankfully this never came to pass. Even though I will likely never need anything from these files, I can’t ever seem to find a decent middle ground between ‘get rid of everything’ vs ‘hoard everything’. I especially don’t want to dispose of anything vaguely medical just in case. ‘Just in case’ of what, I still don’t know…

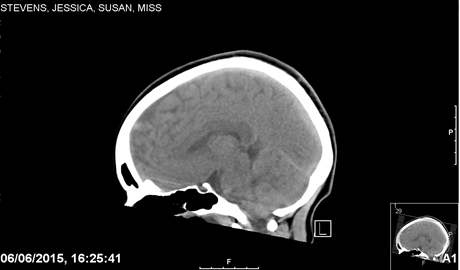

I have hundreds of NHS images/x-rays of my brain from 6 June 2015, the day of my accident. This scan is particularly eerie to look at, knowing it was taken roughly two hours after the collision. I have no idea what it shows though (if anything)…

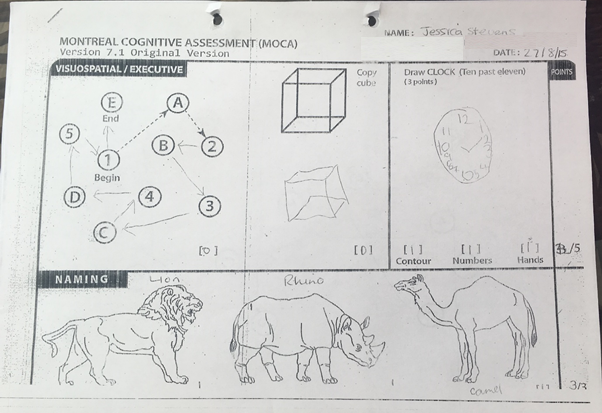

This box also contains paperwork from the occupational therapists I first saw. I can see the date is 27 August 2015, so I completed these tests a couple of weeks after I had first woken up.

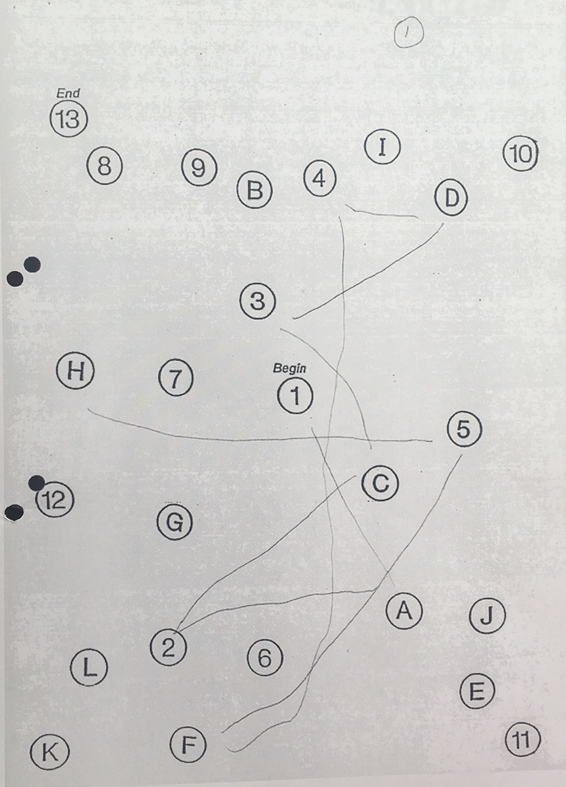

One of the OTs has written the names of all the animals for me, and I drew the clock and the cube myself (I should’ve been an artist…). Then the first activity involved joining the letters and numbers together in alphabetical to numerical order (so 1 – A – 2 – B etc). At least I could successfully complete a small version of this activity, as I definitely couldn’t complete the bigger version later:

I noticed these tests had a name printed at the top, so I Googled it:

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) – rapid screening instrument for mild cognitive dysfunction. It assesses different cognitive domains: attention and concentration, executive functions, memory, language, visuoconstructional skills, conceptual thinking, calculations, and orientation.

https://www.mocatest.org/

Even though it could be seen as childish to have to name animals, this therefore shows how complex, delicate and intricate the brain is. If I had forgotten what a rhino was, this could have meant I had forgotten further ‘basic’ information. Such a simple test therefore indicated how badly my memory had been affected. It is incredibly fascinating to think that an injured brain might not be capable of ‘seeing’ or understanding the depth perceptions of drawing a cube. I obviously didn’t fully understand it, as I didn’t realise that I had missed out a whole line, so this highlights clear initial damage to my conceptual thinking in particular.

Again, looking back at this test is eerie to me: such simple activities are often completely impossible for someone with a brain injury to complete. Looking back at this paperwork does make me a bit sad seeing that I used to be a lot worse, but it also makes me realise how lucky I’ve been and how much progress I’ve made. (I also knew it would eventually be worthwhile to keep paperwork from years ago…)